Drones and the Coronavirus: Do These Applications Make Sense? (Updated)

April 9th, 2020

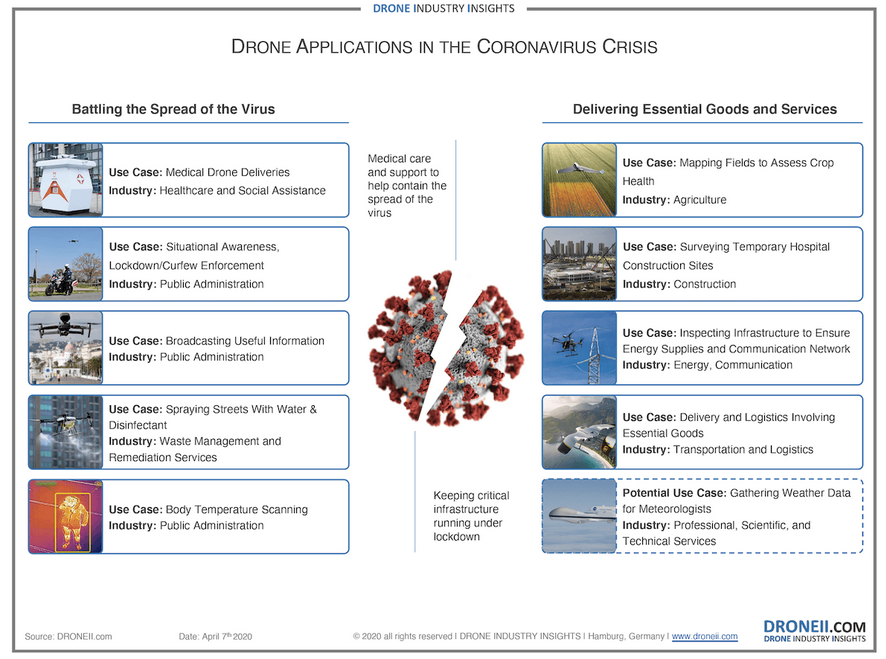

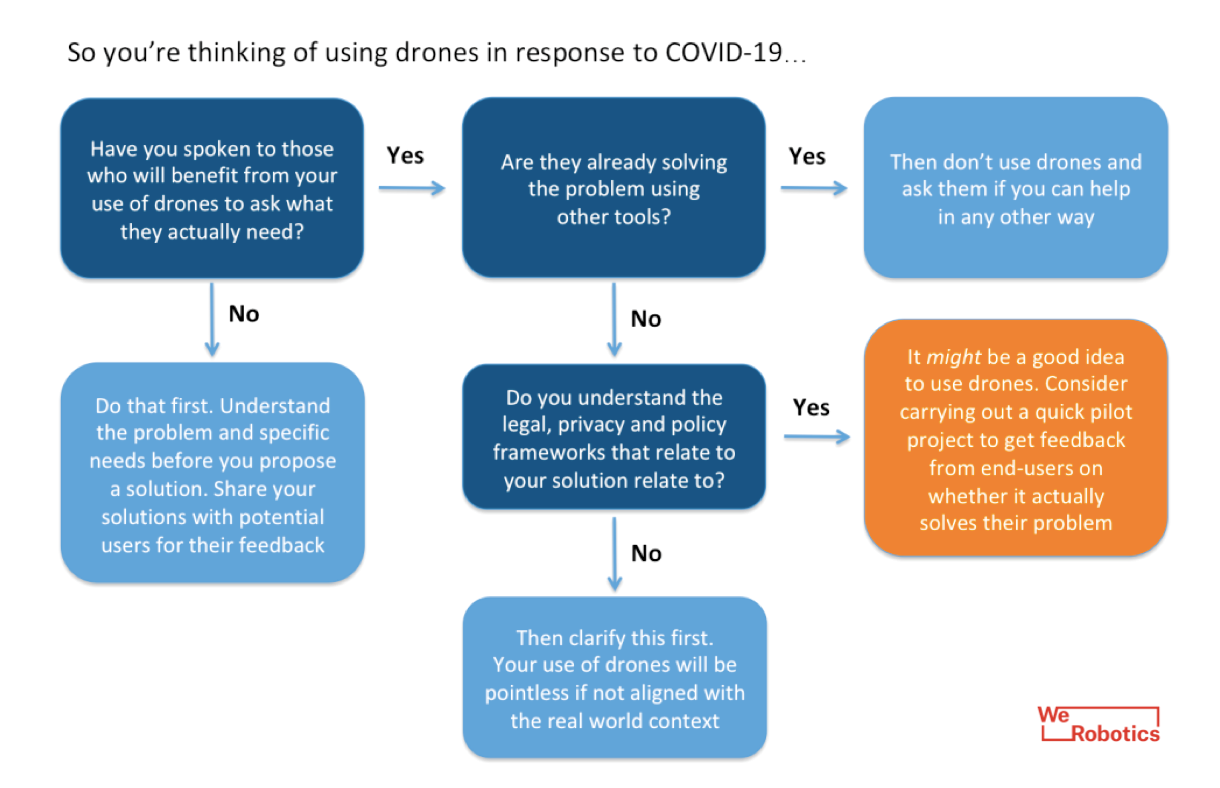

Want to use drones in response to COVID-19? Then read our previous post to inform your decision-making. We also published this follow-up post to suggest that drones may add more value later in adjacent crises. We wrote these posts to encourage more critical thinking around the use of drones in response to the pandemic. We don't have all the answers, of course, but we do have questions on some of the applications that several drone companies and other organizations are promoting. The figure below from Drone Industry Insights (DRONEII) does a great job collating what we've come across in recent weeks.

The applications proposed under "Delivering Essential Goods and Services" on the right-hand side are already mature applications that existed years before the pandemic. As such, the use of drones for agriculture, construction, infrastructure inspection, deliveries of essential goods and the collection of meteorological data during the pandemic can certainly have a positive impact. Take this case from Argentina where aerial data has reportedly been used to accelerate the construction of emergency hospitals, for example. To this, one could add the use of drones to collect detailed spatial data critical to understanding any linkages between disease transmission and environmental factors. One could also add the use of swarming drones to thank health workers. As discussed here, some of these applications may become even more useful when humanitarian disasters impact countries already struggling with COVID-19. In contrast, the applications listed under "Battling the Spread of the Virus" are somewhat more novel, as is the use of pollinating drones to fill the COVID-19 labor shortage. We thus welcome input on those specific applications along with any others that are being overlooked. We'd be especially grateful for any additional evidence there may be to better evaluate the effectiveness of all these applications. We will update this post regularly as new evidence comes to light.

Spraying

It appears there is little to no evidence that outdoor spraying of disinfectants or other substances (by hand or by drone) has any impact on reducing the transmission of the novel coronavirus. On the contrary, this fumigation could create public health problems and add to environmental pollution. As The Lancet Journal on Infectious Diseases clearly noted on March 5, 2020, "air disinfection of cities and communities is not known to be effective for disease control and needs to be stopped. The widespread practice of spraying disinfectant and alcohol in the sky, on roads, vehicles, and personnel has no value; moreover, large quantities of alcohol and disinfectant are potentially harmful to humans and should be avoided." The City of Mumbai has decided not to use drones to disinfect containment zones, noting that "drones are ineffective in cleansing major touch points which have been identified across the containment clusters. It will release the disinfectant on rooftops or surfaces where the virus is not present, rendering the activity completely useless."

While some have suggested that outdoor spraying may help reassure local communities that the government is in control and responding, could this potentially create a false sense of safety and thus dis-incentivize physical distancing? On the other hand, the emotional reassurance and peace of mind that the spraying gives can provide crucial psychological relief, which is key to resilience. That being said, there are other ways to reassure communities that don't involve the use of drones. Others have suggested that the spraying can keep rodents away. But thus far, only one preliminary study has been carried out, which suggests that cats and ferrets are more susceptible to being infected by COVID-19 compared to dogs, pigs, chickens, and ducks. We have not found any scientific studies thus far that assess the transmission of the novel coronavirus from ferrets or cats to human beings.

In sum, governments and drone companies should cease using drones for aerial spraying in response to the pandemic before more problems arise as a result. Take the recent incident in Lima, Peru, where a drone company spraying disinfectants ran into a power line. As a result of this incident, the government has now made it a requirement for operations to secure a special permit until July. It is unclear just yet how easy it is to secure such a permit or how long it might take. According to one colleague, "We were working really hard to help the country in this emergency and now apparently we won't be able to do it."

Indoor spraying is a different question since there are urgent public health reasons to disinfect indoor surface areas. It remains to be seen whether aerial or ground robots are significantly safer and whether they can be more effective at indoor spraying compared to more conventional means. Does the use of drones in this case save time (even when training time is factored in)? Does it save on costs? Is the technology readily available?

One company is offering to sterilize indoor spaces by using a "semi" manual drone to emit ultraviolet waves. While UV light does kill germs and other viruses, there have yet to be any conclusive tests showing that UV light can kill the coronavirus. Even if UV light does kill COVID-19, this prompts another question: how long of an exposure (minutes) is required for this UV light to destroy COVID-19? The Indian military claims that their hand-held "UV gun" can fully sanitize a surface within 20 seconds from 15 centimeters away. In contrast, this study in the scientific journal Nature argues that the exposure time must be 30 minutes to be effective. Due to battery limitations, indoor aerial drones are unlikely to have more than ~20 minutes of flight time. The CEO of the drone company championing their UV-enabled drone expects a flight time of 10 minutes for their "traditional" missions" but typically go with 8 minute flights. According to the CEO, their drones reportedly disinfects an area of 2 meter by 2 meter in 5 minutes. At this rate, one critic notes that it's going to "take a long time and a lot of battery charging to clean a big area like a hospital." It may thus take far longer for a drone to cover each area of concern within a given room. So ground robotics may tentatively be a better fit. A Danish robotics company claims that it takes their autonomous ground robot 30 minutes to kill COVID-19. In any event, if UV light is effective against the coronavirus, it should be noted that not everyone will be able to afford these sophisticated ground robots. (Epilogue: this new research at Columbia University is worth following).

Temperature scanning

It is unclear how valid, reliable, or cost-effective the current technology is for very high-resolution remote scanning at a distance. For example, can relatively affordable sensors distinguish between a body temperature of 37.2C and 38.0C from 50 meters away, let alone 10 meters? According to DJI, these drones would requires special firmware and would need to be operated less than 2 meters of an individual to get a reliable reading. As such, it is unclear what this aid organization in Kenya is hoping to achieve with their DJI drone, or whether this application in China makes any sense. Engineering a drone solution that actually detects fevers remotely is a non-trivial and possibly costly undertaking. One company has already been caught selling a fake COVID-fever detection camera. This has not discouraged other companies and universities from giving it a go, however.

One such drone company is based in Canada. According to their CEO, "just because you have a thermal camera doesn’t mean you can detect a fever. It’s about being able to take all those factors, such as respiratory rates, heart rate, blood pressure and skin tone, to determine if it’s actually a fever or not. To detect heart rate, for instance, AI will analyze both movements as well as color changes around the nose and under the eyes. A directional microphone that cancels out the noise of the pandemic drone’s propellers might pick up the sound of a cough of sneeze. It will act in concert with image analysis that detects the way people move when they cough or sneeze." The project is a joint effort with the University of South Australia, which has already developed some of the AI solutions necessary for the "pandemic drone". The team at the university also plans to develop "a deep learning-based gesture sensor will help the system detect people's coughing and sneezing movements—two very visible signs of a respiratory illness." The professor leading the applied research says the overall approach is really about "mapping the human landscape looking for the virus."

At first glance, however, it appears that the bulk of the university research driving the prototyping is based on experiments with individuals standing motionless in a lab and within 3 meters of the sensors. (Many thanks to @faineg for these insights on the academic research). These indoor, lab-based experiments on stationary objects within 3 meters are a far cry from what the drone company claims it will do in coming weeks: correctly detecting fevers from 58 meters away, outdoors in an uncontrolled environment on subjects moving in different directions and at different speeds. Besides, the latest research published by the university (October 2019) on their experiments concluded that they "still require research to enable the technology to mature into many real-world applications." More specifically, to make this work for uncontrolled environments in which sensors and crowds are moving, they still need to figure out how to overcome technical challenges related to "automatic multiple regions of interest (ROIs) selection, removal of noise artifacts by both illumination variations and motion artifacts, simultaneous multiple person monitoring, long distance detection, multi-camera fusion ." What's more, they also need to get their hands on "publicly available datasets" to train their algorithms for remote, outdoor detection. In sum, this technology doesn't seem to be anywhere close to ready for prime time.

The company's CEO, whose previous track-record raises some questions, wants to see this technology "installed on thousands of drones and millions of camera networks." In the highly unlikely event that the technology can actually be built as advertised, what are the privacy implications of using a drone capable of automatically detecting fevers, coughs and sneezes from a distance? The solution described above is highly intrusive. From the CEO: "It's not our intent for people to be singled out. The idea here to just provide data so that the policy can be set and actions can be taken on a broader basis." This is hardly reassuring (classic understatement), which explains why an initial roll out of the technology in Connecticut was shut down. Could it also be that the Westport Police, which had teamed up on this trial, realized that the technology was not working as advertised?

Either way, not everyone develops a fever as soon as they're infected with the coronavirus, nor do they start coughing or sneezing right away. One of the early warning signs of COVID infection seems to be losing the sense of taste. At this rate, given all the hype around drones and COVID-19, it may just be a matter of time until someone says they can develop a drone to automatically detect lack of taste. Even if there were a breakthrough in the remote fever-scanning technology in the future, then what? For example, someone with a high fever and a cough walks down an alleyway. They are by chance spotted by a "pandemic drone" that detects the fever and a cough or two. Now what? It's relatively easy hide from a drone in an urban environment, even in rural areas. We've learned that one aid organization is discussing the possibility of using such a drone in refugee camps. Assuming this drone sees the light of day, could this application potentially help improve public health surveillance in refugee camps? If so, informed consent would obviously be essential. What if 18% of refugees in different parts of a camp decide to opt out, then what? How does one ensure that the drone flying overhead does not capture their health data?

It should be noted that one of the field hospitals in New York City (NYC) is using a drone with a thermal camera for stationary temperature measurement within a 2-meter distance. They've literally placed the stationary drone on a counter. Individuals stand in front of the drone to get a thermal reading. Responders at the field hospital reportedly calibrated the difference between temperature readings from the drone's thermal camera with those of a medical thermometer. This means that they may be able to infer the body temperature just from the thermal signature captured by the drone's camera. This application is documented here. We're following up with DJI to learn more about the reliability of the calibration. In the meantime, another important question worth asking is why the field hospital did not use regular medical thermometers to get the temperature measurements? According to one member of the emergency management team at the hospital, "there was no quick fix because body scanners and FLIR was on major back order and were weeks out and reading two thousand thermometers was out of the question; it would just take too long at shift starts, especially morning." They added, "I don’t think a drone should be used to do this for the long haul. However, since we have them quickly accessible in our response cars, we can utilize them until more advanced systems designed for this type of incident become available. It was beneficial to us opening up this medical station to treat patients during this epidemic. Without this the medical station may have remained closed awaiting equipment. It didn’t fly a mission but it’s equipment helped a mission which I find important."

The stationary sensor approach taken at the field hospital in New York combined with the AI being developed by the Australian university may potentially add value in the context of refugee camps if data protection and privacy protocols are carefully followed. This setup would not require a single drone.

Audio broadcasting

We hear mixed results in the use of loudspeakers on drones to encourage physical distancing and staying home. As noted here, many of these drones appear to be the DJI Mavic 2 Enterprise, which "comes equipped with a one-way, 100 decibel speaker capable of playing custom voice recordings, which allows the drone pilot to talk to someone on the ground (or play a series of recordings). This is quite useful for people like firefighters and search and rescue workers, who can use the drone to issue instructions and orders from afar." But how useful is this drone application in response to the coronavirus? There are plenty of other ways to get the word out, including radio.

This largely depends on the anecdotes one prefers, i.e., it depends on selection bias. In some of the video footage we've seen, it appears that those who hear these warnings from the sky don't actually change their behaviors. Some passersby take videos of the drones with their smartphones but otherwise go on as before. In other cases, the presence of loudspeaker drones to encourage physical distancing have the opposite effect. In Brazil, for example, the broadcast-drones operated by authorities in Rio prompted curious crowds to gather: "the street was full of onlookers, who gathered to observe the novelty." This explains why the national police in Rwanda is asking residents not leave their homes to view the drones when the latter fly over their neighborhoods. From the Rwandan National Police: "Don't gather in large groups when drones deliver messages." As one Rwandan citizen commented, however, "this sounds impossible especially to people who have never seen them before." Another observer noted that "the idea was a fabulous one we appreciate but the drone was louder than the microphone." The police used megaphone fastened to the bottom of a larger DJI Matrice 600 drone for these public announcements. From a colleague in Kigali: "Here in Rwanda we have police drones with megaphones telling people not to gather in groups – not sure why they thought the pickup-trucks with massive speakers were not being effective enough we could hear those from miles away." In contrast, a colleague in Kathmandu noted that she had an easier time hearing the public announcements broadcast by drones compared to those from cars. As such, the type of drone, loudspeaker and megaphone used will influence how audible and understandable the broadcasts are.

It is worth noting that the 100-decibel speaker on the Mavic drone is a "fairly directional speaker" and is most effective when pointed at a 45 degree angle, according to a colleague. Here's an example of the Mavic being used in France to encourage residents to stay home (the announcement begins around 22 seconds into the video). While the drone's propellers do make an annoying sound, the announcement is audible when the drone is pointed at you, which some argue is "creepy in a way that is alienating, in the midst of a crisis in which human connection is both dangerous and critical. It is not a recipe for fostering public trust. During times of fear and uncertainty, human beings become even more reliant upon personal relationships and trust ." This is particularly true for marginalized, at-risk communities. As noted here, "the person-to-person approach, rather than an impersonal drone, is much more likely to elicit the kind of outcomes that I think people would be hoping for in this situation." This person-to-person approach requires "more of an investment of people and it does require putting some of them at risk, but if you are choosing to send out a drone instead of a person, then you have to question—is that just transferring the risk to the people experiencing ? And is that a fair or an ethical thing to do?”

On the other hand, we hear from our colleagues at India Flying Labs that this application of drones has been relatively effective in certain parts of India, and that many police chiefs are actively asking for drones with loudspeakers to carry out their public awareness efforts. Over in Kenya, this aid organization is using drones with speakers to "remind residents in the informal settlement of Kibera about the importance of hand-washing, physical distancing and the use of masks." They did this while distributing food in person to hundreds of vulnerable families. We need more information to better understand what makes this application impactful in some cases and not in others. How do cultural and historical factors influence the impact of this application? What about urban density and socio-economic demographics? Is there a demonstrated need for the use of "speaker drones" in refugee camps?

It is important that we keep collecting anecdotes and any available data to build more of an evidence-base and to compare this evidence with traditional solutions. Over in Tunisia, it is unclear whether this ground robot (equipped with a camera, thermal sensor, loudspeaker, and microphone) is very effective, for example. Why not merely use a police car with similar sensors? In the US, the Daytona Beach Police Department notes that using drones with loudspeakers "to address large gatherings, Officers may not have to be put at risk walking into the crowd." Again, why not use a police car with the windows up? Also, per the note from Kigali, the sound from megaphones can travel a long distance, so why not use those? There may well be good answers to these questions, which could make the use of drones very compelling in these cases. For example, megaphones alone do not provide the kind of situational awareness that drones with loudspeakers and cameras can provide in real-time. By providing a bird's eye view, drones also offer a greater level of situational awareness compared to the vantage point from police cars. When coupled with loudspeakers, it's easy understand why law enforcement officers become even more keen to use this integrated aerial technology.

In some cases, the messaging itself may need to be carefully crafted to maximize the potential for behavior change. Just repeating the same messages over and over, "stay home, keep your distance," may not be as effective all the time since many have already heard these same messages from other sources. First, the messaging should be used to offer an information service, i.e., to provide "news you can use" to local communities; to be an authoritative source of information. Second, in some contexts, the messaging itself may benefit from being crafted in such a way that it resonates at a hyper-local level. Draw on specific local customs and local traditions, and/or have local celebrities do the messaging. Either way, crafting different messages for different age-groups and/or separate messages for men and women is considered good practice when communicating with disaster affected communities.

Cargo delivery

Using cargo drones to deliver essential medicines and to collect patient samples for COVID-19 testing is being widely promoted. Delivering sandwiches using drones is one thing, but anyone who has been operationally involved in setting up cargo drones operations knows that doing so for medical deliveries can take a significant amount of time. Also, the local availability of reliable and affordable cargo drones, let alone trained cargo drone pilots, is limited in many countries. In addition, it is unclear whether the majority of Civil Aviation Authorities (CAAs) are likely to provide fast track options for flight permissions, even during a pandemic. They have rarely done this during previous humanitarian emergencies, quite on the contrary, some CAAs add restrictions on drone operations during disasters. That being said, the pandemic is not a typical emergency. Furthermore, the unparalleled reduction in air traffic does make the use of drones relatively less risky. As such, if the political will is there, then it is entirely possible that regulatory solutions will be "fast" tracked. In the US, for example, the Federal Aviation Authority (CAA) is granting "drone flight waivers to help fight the COVID-19 pandemic". From the FAA: "We may be able to enable some things in response to the COVID emergency that would not be approvals that would maintain after the emergency . "We have a decrease right now in what we're seeing for air traffic, so some of the liability and air risk that we might previously have had at a higher level could potentially be mitigated just by the fact we don't have as many aircraft out there flying." In addition, Sri Lanka's Civil Aviation Authority is actively calling (crowdsourcing) drone pilots to assist in the response to COVID-19. India's CAA has also announced exemptions for drone use in response to the pandemic.

In most cases, the deployment of new cargo drone projects for high frequency deliveries in response to the pandemic is still expected to face several important constraints. That being said, for cargo drone projects that are currently (or recently were) operational, like Google's Wing project, these can be more easily ramped up or repurposed to support the pandemic response. Zipline, for example, is looking to use their drones to deliver Personal Protective Equipment (PPE). On April 16, 2020, a representative from Zipline announced on a webinar that the company's hub in Ghana is now able to deliver patient samples for rapid COVID-19 testing. The patient samples are transported through conventional (?) means to Zipline's droneports (fulfillment centers) after which they placed in their drones and flown to the national laboratory for testing. As noted by a colleague: how transformational the fulfillment centers are in the entire lab supply chain is unclear. This video reportedly shows one of the first Zipline deliveries of patient samples for rapid testing. See also this video and this news report. We will be sure to update the blog as more information becomes available. In the meantime, foreign companies with significant resources and experience, like Zipline, may also be able to set up new cargo drone services in new countries relatively quickly. Even then, however, if/when the relevant medicines to help treat COVID symptoms are unavailable, or if insufficient tests are available to test for the virus, then the added value of drones may be limited.

Another important point to keep in mind is that hard-to-reach communities do not necessarily benefit from existing drone deliveries. It comes down to business models. Companies like Zipline set up their droneports in areas that require high-frequency, high-volume deliveries as this creates a worthwhile return on investment. This explains why Zipline's droneports are designed to make some 600 deliveries per day within a ~75km radius. To this end, it is unlikely that companies like Zipline would invest in building a droneport in an area that requires some 600 deliveries per year, let alone 600 deliveries per month when their droneports can make well over 15,000 deliveries monthly. Remote villages are small and dispersed. As such, the demand per village for medical supplies is nowhere near as high as the demand per town or city. One might well suppose that hard-to-reach indigenous communities like those in the Amazon Rainforest are completely isolated world and thus the safest from the pandemic. Unfortunately, these remote communities are already being hit by the coronavirus.

This explains why WeRobotics has been asked by a prospective partner to explore the possibility of using cargo drones to deliver a specific medicine that can help patients suffering from the coronavirus. This partner already has the medicine in stock. The challenge they face is in delivering this medicine to some of the very remote, hard-to-reach communities they serve. We'll provide updates on this possible project via this blog post should said project continue to move forward.

In the meantime, there are of course other needs for medical deliveries, such as transporting essential medicines into quarantine areas. We also hear from Panama Flying Labs that the lock-down there restricts movement based on the ID number on your national ID card. Everyone is assigned a specific window of time when they can leave their homes for essential reasons based on their ID numbers. This poses a major challenge to those suffering from chronic illnesses who need their medications refilled on a regular basis. So Panama Flying Labs has been asked to look into possible cargo drone solutions to address this problem. It remains to be seen whether doing so will be logistically feasible and whether using cargo drones will add value compared to traditional delivery methods. We also hear from public health experts that the lockdowns have placed immunization and vaccination programs on hold in many countries. As such, they expect a number of outbreaks like polio outbreaks to occur in conjunction with COVID-19. This is why Cameroon Flying Labs is keen to move forward on this project with the Gates Foundation, Center for Disease Control (CDC) and the World Health Organization (WHO) as it focuses on polio samples.

Please see this dedicated study on how delivery drones are being used in 10+ countries in response to COVID. For more on the use of medical cargo drones in public health, please see our peer-reviewed online course on the topic.

Surveillance

Drones can enhance situational awareness. This explains why many have advocated for the use of drones to help enforce lock-downs, sanitary cordons and curfews during the pandemic. In West Africa, for example, Flying Labs have teamed up to monitor remote border crossings using their drones. This is being done directly with relevant authorities. At the request of local authorities in Lima, Peru Flying Labs is using drones to count the number of vehicles, people and market stands to monitor how well the lockdown is being respected. In the US, drones are reportedly making it easier for police to see into certain areas where access by patrol cars is more difficult, including tight spaces between buildings and behind cars. Some have used thermal cameras to carry out this monitoring at night. Some are reportedly using night-vision. While surveillance drones may also be relatively effective (?) in some places like Kohima or Delhi, they raise important concerns around data privacy and data protection. To be clear, these concerns are not limited to Personal Identifying Information. They also include worries around demographically identifiable information. Alas, data privacy and protection issues are rarely addressed by those advocating for drone-based surveillance, particularly drone companies. It should also be noted the majority of police forces that use drones do not mark them in any way to distinguish them from other drones being used for other purposes. As one colleague asked, "Like if I saw one how would I even know it was a police drone? Or if I heard an announcement claiming to be the police?" Meanwhile, there are increasing concerns that many governments are taking advantage of the pandemic to impose harsher surveillance measures that may persist well beyond the end of the pandemic. The French Government, for example, spent four million Euros to purchase 651 surveillance drones in the middle of the pandemic.

Meanwhile, in Malaysia, a foreign drone company donated over USD 500,000 worth of drones and sensors to police in Kuala Lumpur for surveillance purposes. Some of these drones include tethered drones that enable continuous surveillance. In their 18-page marketing brochure that promotes the use of drones to fight COVID-19, the word "privacy" appears a total of zero times. The company argues that drones enable operators to maintain safe distance between law enforcement personnel and crowd. True. So do police cars. Why not use police cars or motorbikes to do the patrolling in Kuala Lumpur (KL)? Is there a shortage of police cars and/or police officers? There's little to no traffic in KL right now, so using police cars now is especially efficient, which means fewer cars and drivers are needed. Also, those cars cost $0 to purchase since they're already part of the police force. As an aside, we've seen multiple photos of drone experts huddled together with police and other government officials to show them the live feed from their surveillance drones overhead. This does not qualify as physical distancing; nor does this when drone operators startle individuals who then crowd together.

Again, however, this does not mean that drones cannot be used to augment surveillance measures in a responsible manner, it simply means that we need more information on local context, actual needs, priorities, alternatives, politics, culture, history, etc., to understand the possible added value of aerial robotics in the fight against the coronavirus. As such, there may well be compelling reasons to use surveillance drones in KL, and perhaps in informal settlements like Kibera since access can be more challenging in those contexts. We should both collect and question these reasons, however, and not simply assume they are valid. As one Flying Labs leader in Asia put it, we need "social science, behavioral science, public health, data science and political science" to better understand the value added of these drone applications.

Aerial QR Codes

In Shengzhen, China, local police have reportedly used drones carrying posters of QR codes. The QR code is used as a registration system for drivers returning to Shengzhen. The police have used this to monitor population movement into the city. The drones are flown near toll booths at highway exits. If we understand correctly, drivers are required to scan the QR code using their smartphone so their movements and risk-levels can be tracked. It is unclear why a drone might be more effective than alternatives, such as adding the posters to the toll booths themselves. Perhaps the novelty of using drones is better at capturing the attention of drivers? Or is the use of drones for QR code monitoring meant to remind drivers that they are being monitored? Chinese authorities have made extensive use of QR codes in efforts to prevent and control the pandemic prior to using them on drones. Many have been alarmed by what they warn is clear government overreach.

Connectivity

While not documented in DRONEII's diagram above, we're starting to get some interest in the application of "flying cell phone towers" in response to the pandemic. More on this drone-enabled solution from our technology partner here. These tethered drones, which weigh 12kg and carry access points that weigh up to 10kg, are connected to an electrical source and able to remain in the air for six consecutive weeks. We were recently on a call with key partners to discuss the possible deployment of these tethered drones to provide connectivity in refugee camps where conventional communication infrastructure is not yet in place. The drone-enabled connectivity would give local communities the ability to communicate with each other remotely (physical distancing) rather than in person. In addition, humanitarians could use the drones to communicate more directly and frequently with local communities, sharing important updates and recommendations. Communicating with disaster-affected communities is essential during emergencies. Given that access to electricity can be a challenge in some refugee camps, it remains to be seen whether these flying cell phone towers can play a meaningful role in supporting the COVID-response in refugee camps. In terms of alternatives, could Google Loons be more effective?

Mapping

The use of aerial mapping to enable physical distancing is somewhat of a new use-case for drones. Population density is one of several factors that determine how vulnerable inhabitants are to the virus. As such, an Indian drone company has been providing police with high-resolution maps overlaid with population data to support a range of efforts. These maps are reportedly being used to plan "the essential movement for delivery partners, placement of barricades, social boundaries, management of society gates (whether they need to be closed or opened) and also which roads need to be blocked . The police are also using the maps to place physical distancing markers and to decide where to set up isolation, screening and treatment centers. In highly dense and-thus-vulnerable areas such as informal settlements, the police are making use of the high-resolution maps to give them "a clear picture for planning groceries movements, quarantine centres and workforce allocation." The Indian drone company was also asked by the police to "mark nearby hospitals and police stations from hotspots and the shortest running routes for easy movements in case of an emergency." When asked what they would have done if drones had not been available, one police offer replied, "We were carrying out all sort of planning on printed maps, but this online tool by an Indian company Indshine gives us the flexibility to work from anywhere." Local government in Punjab asked another drone company to "create public-facing dashboard for India, and a district-wise one for Punjab, specifically. Over the course of time, the scope of work was increased to include geo-fencing of quarantined patients, cluster analysis of the spread, location tracking with call records data, and predictive analysis for spatial-spread based on those parameters. "Providing a central dashboard that can aggregate, and create, reliable master geo-databases to provide an accurate estimate of the situation to decision-makers has turned our business into a complete war room solution, and we’re offering this for free.”

Conclusion

To be clear, we are not public health experts ourselves (although several leaders of Flying Labs are medical doctors). The evidence currently available to evaluate the impact of some of the drone applications above is particularly thin. On the plus side, this means that further evidence may well confirm that they are impactful. Then again, further evidence could conclusively show the lack of meaningful impact. This explains why thinking about data collection now rather than later is so important: "Being able to understand what works and doesn’t in specific contexts now will not only help throughout the entirety of the COVID response, but also long term. This is an important time for the sector to come together and share." Doing so will help inform more effective users of drones over the short-term and medium-term. Over the long term, some of the same drone-related activities could be extended to support economic recovery and resilience-building by incubating locally-owned drone businesses, for example. Either way, it is imperative that the response be a local-first response, i.e., that those using drone technology be local experts who have deep local knowledge, and who understand local dynamics and local communities along with their actual needs. It is equally important that the response follow the Humanitarian UAV/Drone Code of Conduct (UAVCode).

We should also note that when some governments and local authorities instruct local drone experts to spray disinfectants to contain COVID-19, for example, these local experts may have no choice. This may also be true for some of the other applications listed above. That being said, at the very least, it is our collective responsibility to inform these authorities about the expected added value of these applications based on the existing science and evidence. Naturally, all this needs to be deeply rooted within local context, politics and culture.

What is important is that we keep learning at a rapid pace and take in all new forms of evidence to review the uses of drones in response to the pandemic. This doesn't mean that drones cannot play a decisive role in supporting the response to COVID-19; it simply means that more critical thinking is necessary before launching yet another drone project to tackle the pandemic. While drones may not add as much value as we'd like in the current phase of the global health emergency, this may soon change. Either way, we'll be sure to continue working with and learning from Flying Labs to document what works and what doesn't work to the best of our abilities. In the meantime, we're fans of what Nepal Flying Labs is doing in response to the pandemic. Given the drastic reduction in air traffic around the capital city, the municipalities in Kathmandu Valley may finally be able to secure flight permissions from the Nepal Civil Aviation Authority, so that Nepal Flying Labs and partners can use their drones to create high-resolution maps of the vast area (pictured above). These very detailed maps have long been needed to inform urban planning projects led by the municipalities. The project was recently featured on Nepali Television. In sum, it is likely that the best use of drones in the time of COVID-19 is not to find "innovative applications" but to do more of what was already working, such as building better datasets for urban planning, climate change adaptation, rapid damage assessments, improving agricultural yield, delivering medications and collecting patient samples.

Recent Articles