The Latest on Drones for Disease Vector Control

January 8th, 2018

We had the distinct honor of serving on the expert panel of judges for the prestigious International Drones and Robotics for Good Awards in Dubai for 2 years. It was there that we first came across the path-breaking work of the Insect Pest Control Laboratory (IPCL) of the Joint FAO/IAEA Division of Nuclear Techniques in Food and Agriculture (NAFA). Their proposed solution: to fight Zika and other mosquito-borne diseases by using drones. We were impressed with their innovative approach and pleased that their pitch was recognized as such by my fellow judges in Dubai: the FAO/IAEA team was selected as one of 10 semi-finalists from over 1,000 competing teams.

We therefore reached out to IPCL when USAID launched their Grand Challenge on combating Zika and related diseases. We were keen to explore whether WeRobotics could help translate IPCL’s pitch in Dubai into reality. To be sure, combining FAO/IAEA’s world renowned expertise in pest control with our demonstrated expertise in the application of robotics for positive social impact could really make a difference. Thankfully, USAID was equally excited and kindly awarded us with this grant to design, prototype and field-test a mosquito release mechanism specifically for drones.

We therefore reached out to IPCL when USAID launched their Grand Challenge on combating Zika and related diseases. We were keen to explore whether WeRobotics could help translate IPCL’s pitch in Dubai into reality. To be sure, combining FAO/IAEA’s world renowned expertise in pest control with our demonstrated expertise in the application of robotics for positive social impact could really make a difference. Thankfully, USAID was equally excited and kindly awarded us with this grant to design, prototype and field-test a mosquito release mechanism specifically for drones.

Mosquitoes are one of the world’s biggest killers, responsible for spreading deadly diseases including Zika, dengue and malaria. Among the many ways being researched to combat this threat is the Sterile Insect Technique (SIT) - flooding the environment with non-biting, sterile male mosquitoes, which after mating produce sterile eggs and a reduction in the local mosquito population. SIT is a complementary tool in pest-control efforts. This form of insect birth control has been used successfully for decades to combat insects, including the Mediterranean fruit fly, the screwworm and the tsetse fly, and is now being adapted to help fight disease-transmitting mosquitos. One of the challenges for the potential use of this technique is efficiently spreading millions of sterile mosquitoes - this is where drones come in. So for the past year we have been working together with IPCL on a drone-based mosquito dispersion mechanism, as part of USAID’s Grand Challenge on combating Zika and related diseases.

You can read here about the motivations behind using mosquito-releasing drones for vector control. As we’ve recently received some media coverage on our joint project (e.g., BBC, IEEE Spectrum, TechExplore, DigitalTrends, International Business Times and Internet of Business) we wanted to share the latest developments on our prototype.

While release mechanisms exist for fruit flies (in particular for manned aircraft), mosquitoes are alas far more fragile. Developing a release mechanism for mosquitoes is a lot more difficult, presenting a number of design challenges ranging from the shape of the mosquito storage unit and its nozzle, to the type of ejection unit used to physically disperse them. Quality of the mosquitoes as they exit the mechanism is paramount; the mosquitoes must be able to find mates, and any damage to their wings or body can prevent them from successfully competing with non-sterile males.

In addition, the mosquitoes need to be kept between 4-10 °C to keep them in a sleep-like state so that they don’t get “active” and hurt each other when placed into the small release mechanism. So the challenge here is to maintain the cold-chain as efficiently as possible; not only during the drone flight, but also during transportation to the takeoff site and setup of the drone platform.

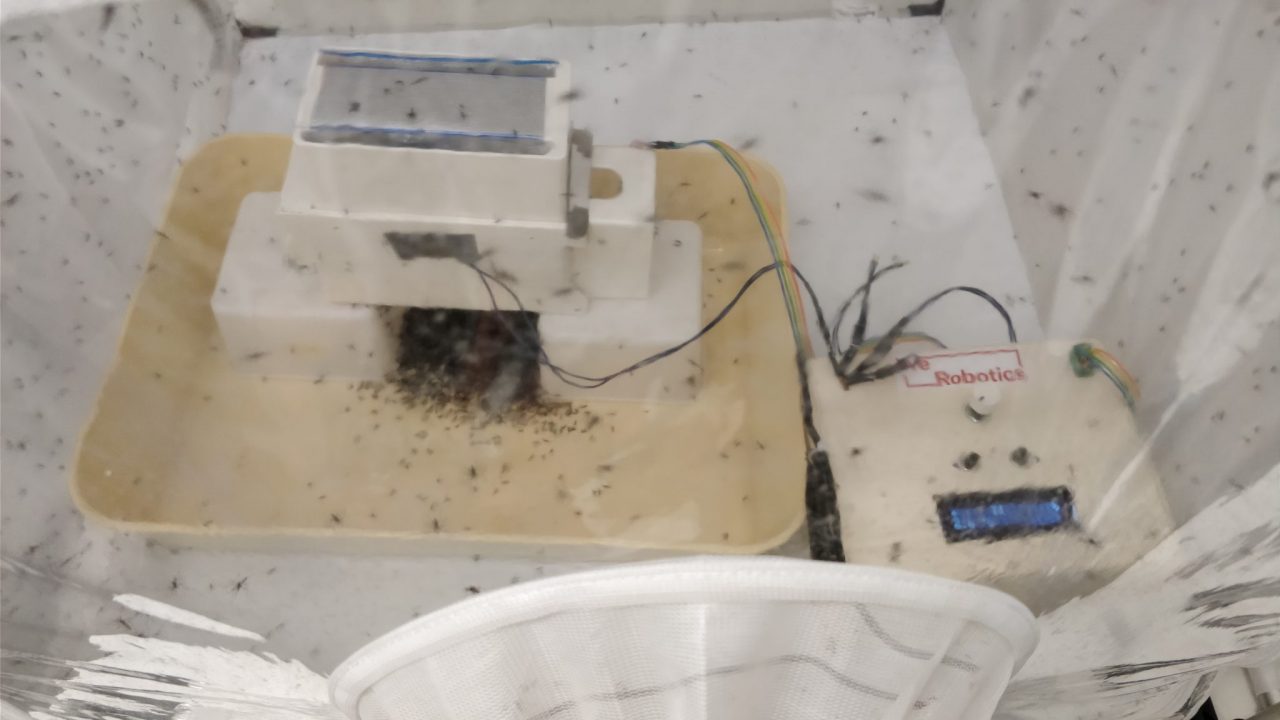

Our immediate direct goal is to release 50,000-100,000 mosquitoes over one square kilometer in a single drone flight. While a range of ejection solutions were considered, we’re currently using a mechanism based on a simple rotating cylinder with small slots that transfers mosquitoes in small batches. This mechanism was developed for other fragile insects within the ERC REVOLINC project (PCT/EP2017/059832). To chill the mosquitoes we’re using a passive cooling technique based on phase change materials.

The first step in validating the system is lab tests. Our partners at IPCL have reared hundreds of thousands of mosquitoes (photo above) and passed them through the device in various configurations, measuring their resistance to the mechanical stress of the mechanism, wind resistance and various other details. The release mechanism was extensively tested with real mosquitoes (Aedes aegypti) at IPCL in Vienna with further tests scheduled for early December.

Lab tests help us characterize our mechanism in controlled conditions, but the real proof of the mechanism’s efficacy must be done in the mosquito’s natural habitat. We are thus finalizing our plans to field test the release mechanism with live mosquitoes in Latin America in early 2018. IPCL will be using mosquito traps during these tests to evaluate the survival and dispersal of mosquitoes from the mechanism, comparing it to ground-based release and giving us clues on the impact of aerially-released sterile mosquitoes on the overall mosquito population.

Stay tuned for the results of our field tests in coming months!

Recent Articles